Exploring stochastic rounding for the lattice Boltzmann method

Published 2025-07-29

Note: this was an undergraduate research project that I supervised. The implementation for this project was completed by David De Le Torre, an undergraduate researcher at MIT. This post aims to both showcase David’s awesome work, and provide utility to the LBM community.

Introduction

An important problem in modern computational fluid dynamics is whether or not we need to carry full double precision (FP64) accuracy. Most of the time, we just end up carrying double precision. However, using single (FP32) or half (FP16) precision, we can exploit available architectures (e.g., tensor cores), reduce memory demands, and increase computational speed. It’s an active area of research in CFD. See these recent articles which explore single and mixed precision for CFD:

- (2024) On floating point precision in computational fluid dynamics using OpenFOAM, by Brogi et al.

- (2025) Effects of lower floating-point precision on scale-resolving numerical simulations of turbulence, by Karp et al.

The effect of floating point representation on the accuracy of the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) was studied fairly methodically by Lehman et al. (2021), the authors of the impressive FluidX3D LBM code. Here’s FluidX3D being used to simulate turbulence around an X-Wing.. Essentially, Lehman et al. showed that error accumulation in FP16 representations is too high, and usually FP32 or FP64 is required. They also came up with their own version of FP32 design for the lattice Boltzmann method.

In this project, we aimed to conduct a similar analysis as Lehman et al. to investigate whether or not stochastic rounding can enable the use of lower accuracy floating point representations in LBM simulations. Check out this blog post, paper, and Julia implementation of stochastic rounding for more details.

I think stochastic rounding is an interesting idea. Essentially, rather than always (i.e., deterministically) rounding $0.7\mapsto 1$, and $0.3 \mapsto 0$, we round them with some probability to these nearest values. For example, $1.3 \mapsto 1$ with probability 0.7, and $1.3 \mapsto 2$ with probability 0.3. The core idea of this rounding algorithm is that it results in a less biased roundoff error, since the rounding is random. For a computation with many iterations (e.g., a CFD simulation, or training a neural network), this results in an overall improvement in roundoff error.

The main research question in this investigation was: for a lattice Boltzmann code, can stochastic rounding reduce round-off errors to the point of enabling the use of lower floating-point representations?

Our main goals were to:

- Implement a stochastic-rounding enabled 3D lattice Boltzmann method code in Julia

- Confirm the results of the above arXiv paper, without the use of stochastic rounding

- Determine if stochastic rounding enables the use of FP16 and FP32 in computational fluid dynamics

- Investigate the error differences when stochastic rounding is used in computational fluid dynamics

The main issue is whether error accumulation with repeated rounding can cause inaccurate simulation results.

Implementation

David implemented a Julia-based LBM solver that allows the user to specify the floating point type used. David’s code is available here.

David implemented the vanilla LBM algorithm, as well as the DDF-shifted version used by Lehman et al. DDF shifting is essentially a clever arithmetic trick that greatly reduces accumulation of roundoff error in the LBM algorithm. You can read more about DDF shifting in Lehman et al.’s paper.

Results

We focused on simulating Taylor-Green vortex decay. This is a simple canonical flow used to test CFD solver implementations. It’s one of the rare cases where we know the analytical solution to the Navier-Stokes equations given a set of initial and boundary conditions, so we can exactly evaluate the error in our simulation.

Here’s essentially the “reference” simulation. It’s a 64x64 grid simulation of Taylor Green vortex decay, with FP64 representation and DDF shifting used.

Here are the results from experimenting with different floating point representations (FP32 and FP16), stochastic rounding (sr), and DDF shifting (shift/unshift). This is over the first few time steps of the decay.

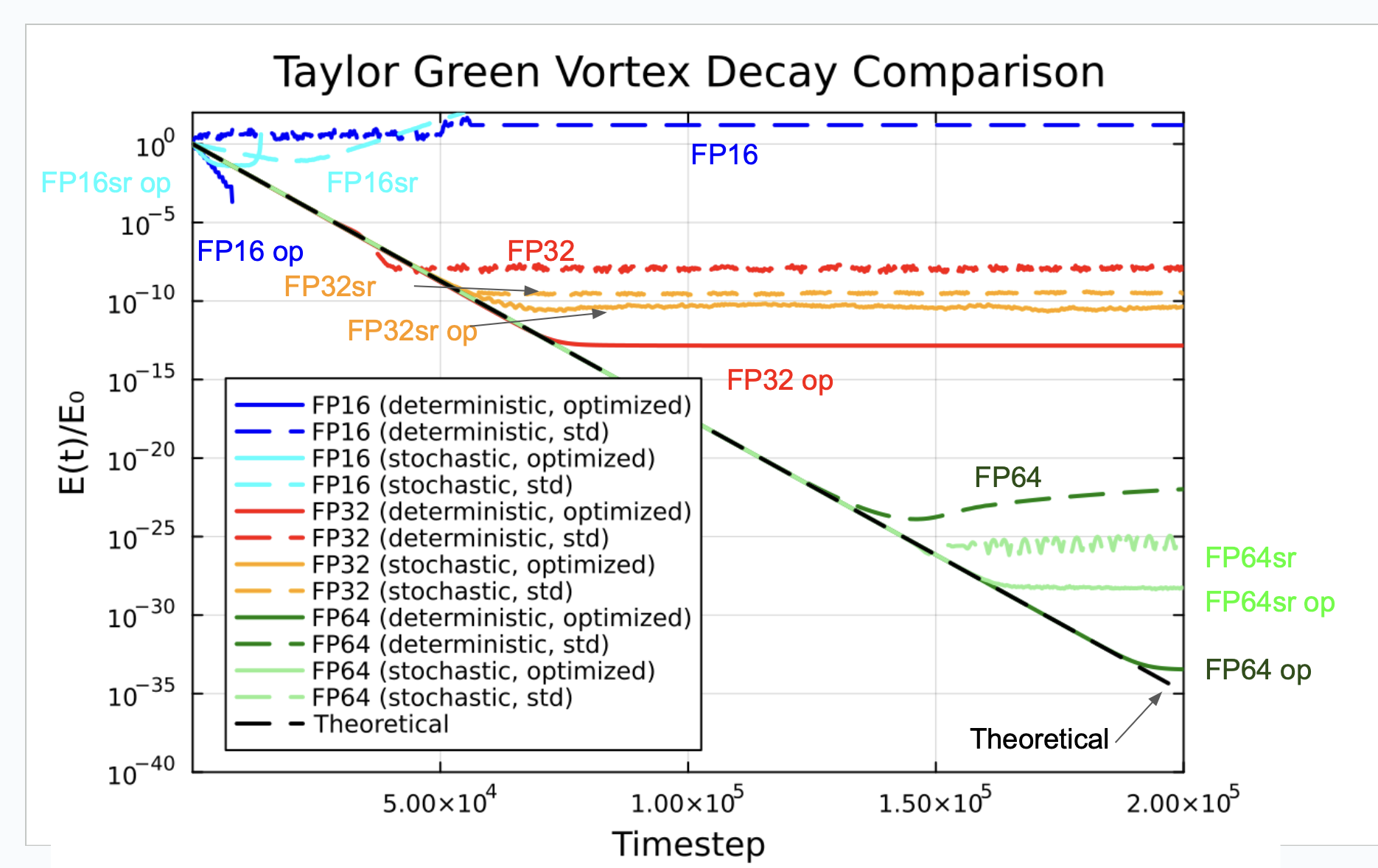

It’s clear that the FP16 case doesn’t decay at all, so it isn’t usable. In a similar manner to Lehman et al., we analyzed the decay in total energy over time as the vortex decays. You can easily see where roundoff error dominates the overall simulation error. The plot below summarizes our results.

The black dashed line is the analytical solution. As the vortex decays, a given line will depart from the black dashed line when the truncation error dominates, and the energy is too small to be computed accurately using the selected floating point representation. “Optimized” in this plot means using the DDF-shifting trick discussed above. “Deterministic” means using standard rounding, and “stochastic” means using stochastic rounding.

We drew the following conclusions from this plot:

- We confirm Lehman et al.’s results that DDF shifting improves the performance of deterministically rounded FP32 and FP64 representations.

- DDF shifting also improves the performance when using stochastic rounding floating point representations.

- Stochastic rounding improves the performance of the vanilla LBM algorithm with FP32 and FP64 representations, but worsens the performance of the DDF-shifted LBM algorithm.

- The high roundoff error in FP16 means that it is unacceptable for use in LBM simulations, even with DDF shifting.

Analysis

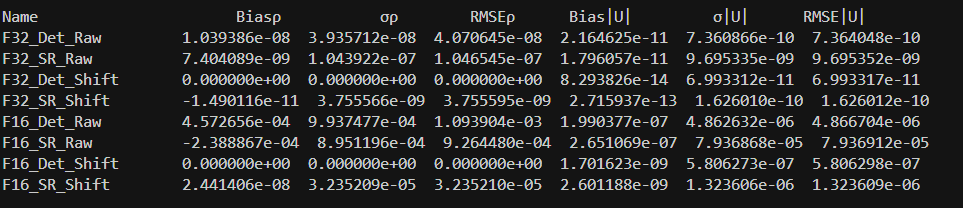

We wanted to investigate in more detail the reasons why stochastic rounding didn’t improve the DDF-shifted LBM algorithm. David found that because DDF shifting greatly reduces the deterministic bias error, there is minimal improvement when stochastic rounding is employed (i.e., there really isn’t any more deterministic bias error to be eliminated). In order to reduce deterministic bias, stochastic rounding adds variance, which in this case worsens performance. See David’s analysis here for more details. The results below show the bias/variance differences in the various algorithms.

Summary

If you’re looking to improve the roundoff error performance of the lattice Boltzmann method, you’re better off using DDF-shifting (see Lehman et al.’s paper). Stochastic rounding improves the performance of the vanilla LBM algorithm. However, it does so by trading increased variance for reduced bias. DDF shifting greatly reduces this bias already, so the increased variance when using stochastic rounding is not helpful.